In the NFL, passing the football is more efficient than running it.

Nonetheless, there are still situations where running is the preferred option, such as third-and-short, and perfectly blocked run plays are the most efficient plays in football. Therefore, running the ball is still worthwhile in the NFL, and as long as it is, steps should be taken to analyze the best way for teams to do so. This article’s purpose is to take steps to achieve that goal.

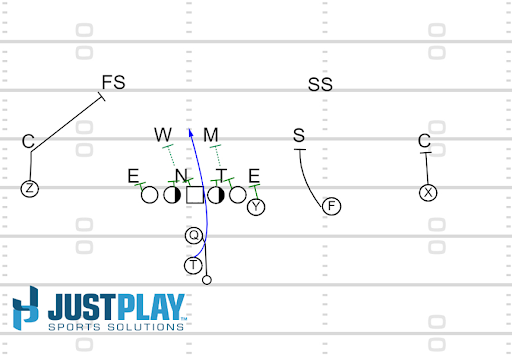

Today, we’ll be looking at running the ball out of single back sets into an over or under front with four down defensive linemen — both out of four-wide receiver formations and those with a single in-line tight end. We will only be considering plays where there are exactly four down defensive linemen — two of which are aligned in a five-technique (outside shoulder of the opposing OT) or wider while a third is lined up in the A-gap (between the offensive guard’s inside shoulder and the center’s outside shoulder) and another is lined up in the B-gap (between the offensive guard’s outside shoulder and the offensive tackle’s inside shoulder). For communication purposes, we’ll be referring to the A-gap defender as a “one-technique” and the B-gap defender as a “three-technique,” but note that the defensive linemen are not necessarily lined up in those exact techniques.

There is no universal terminology in football, as individual defenses have varying methods to set their fronts, so some teams use the terms “over front” or “under front” to refer to different things.

Nonetheless, for our purposes, an over front means that if there is an in-line tight end, then the three-technique is on the same side as the tight end while an under front means the one-technique is on the same side as the tight end.

If there is no in-line tight end, then an over front has the three-technique is set to the field, which means he’s on the side of the field with more space. Thus an under front with no in-line tight end refers to the one-technique being set to the field.

With our definitions established, we can now get into the meat of the analysis. We will be performing a one-sided ANOVA test to see if there is a statistically significant difference in terms of yards gained when running to the one-technique side of the front or the three-technique side.

We’ll break this up by five of the main run concepts charted by PFF (inside zone, outside zone, power, pull lead and counter) for each of the fronts discussed earlier. For the plays that include an in-line tight end, we’ll also break down if the run is going to the field or the boundary (the short side of the field).

We’ll first present each run concept’s definition, if either side should theoretically be more efficient, and whether any differences are statistically significant. Our sample goes from 2016 to 2021.

Note: This does not account for individual running backs, offensive linemen, defensive linemen or box counts; therefore, it will not produce good specific estimates for how much better it is to run to one side or another. However, this will give us directional information on what the biggest differences are when attacking over and under fronts.

Inside zone

The inside zone concept generally occurs when the entire offensive line steps in the same direction and creates double teams along their paths when necessary while the running back aims toward the inside of the formation with the freedom to cut back. PFF specifically charts a play as inside zone if the aiming point is “the first defender on the line of scrimmage (LOS) to the playside of the center.” Against the over and under fronts in our analysis, there will always be one A-gap unoccupied on the line of scrimmage before the snap. The nature of the inside zone concept means that if the offensive line is able to move the one-technique off his spot, then the RB can choose to run through that vacated gap. Therefore, the theory implied by the scheme does not suggest that running to the one- or three-technique is more efficient. The data backs up this theory, as there is no statistically significant difference between running at the one- or three-technique in any of the defensive fronts examined.

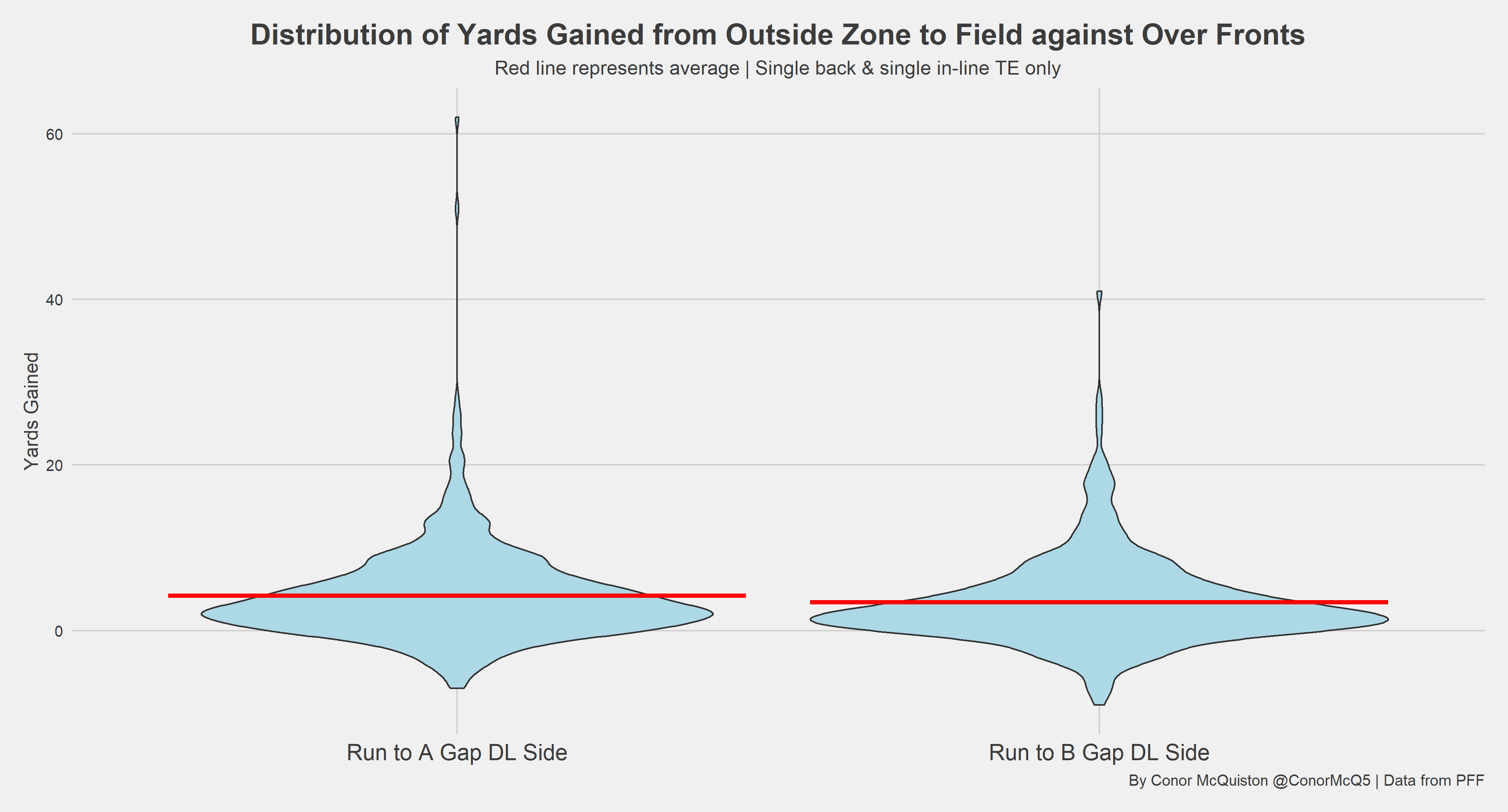

Outside Zone

The outside zone concept, for our purposes, is basically the same concept as inside zone except the running back has a wider aiming point while the offensive line takes wider steps. However, the main philosophical difference is that the outside zone concept’s primary goal is to attack the B-gap, which would imply the most efficient decision would be to run to the one-technique side to attack the “B-gap bubble,” which is the unoccupied space on the line of scrimmage between the one-technique nose tackle and five-technique defensive end.

The only statistically significant difference between running at the three-technique and one-technique is when the offense is facing an over front while utilizing in-line TE and running to the field.

Running toward the one-technique has a 4.24-yard average gain while running to the three-technique produced a 3.44-yard average gain. In the aggregate, both with and without an in-line tight end, running toward the one-technique’s side is more efficient than the three-technique’s side. However, in each individual split, we do not have a big enough sample size for statistical significance (there has only been 275 outside zone from four-wide receiver sets in the sample), and this is further exacerbated by teams biasing heavily toward running at the one-technique with outside zone, doing so 63.5% of the time. This is evidence that this is sensible bias.

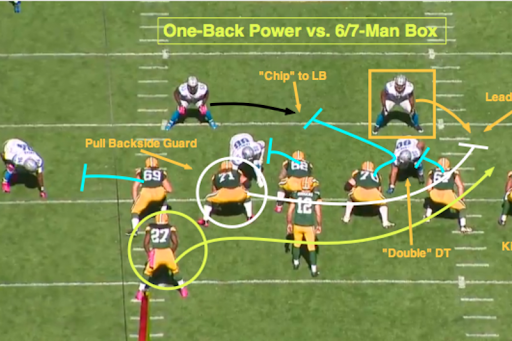

Power

Power is one of the oldest run concepts in football, and the single back variation that we are using is incredibly simple. The play-side offensive linemen block down and try to climb up to the second level while the last play-side offensive lineman on the line of scrimmage kicks out the edge defender and a pulling backside guard leads through the intended hole. This play is meant to run off tackle. It is important to note that PFF only defines a run as “power” when there is a single pulling offensive lineman from the backside; therefore, some plays charted as power — particularly out of four-wide receiver sets — may not match traditional definitions of power.

Due to that, we will only be concerning ourselves with power when it is run out of sets with an in-line tight end.

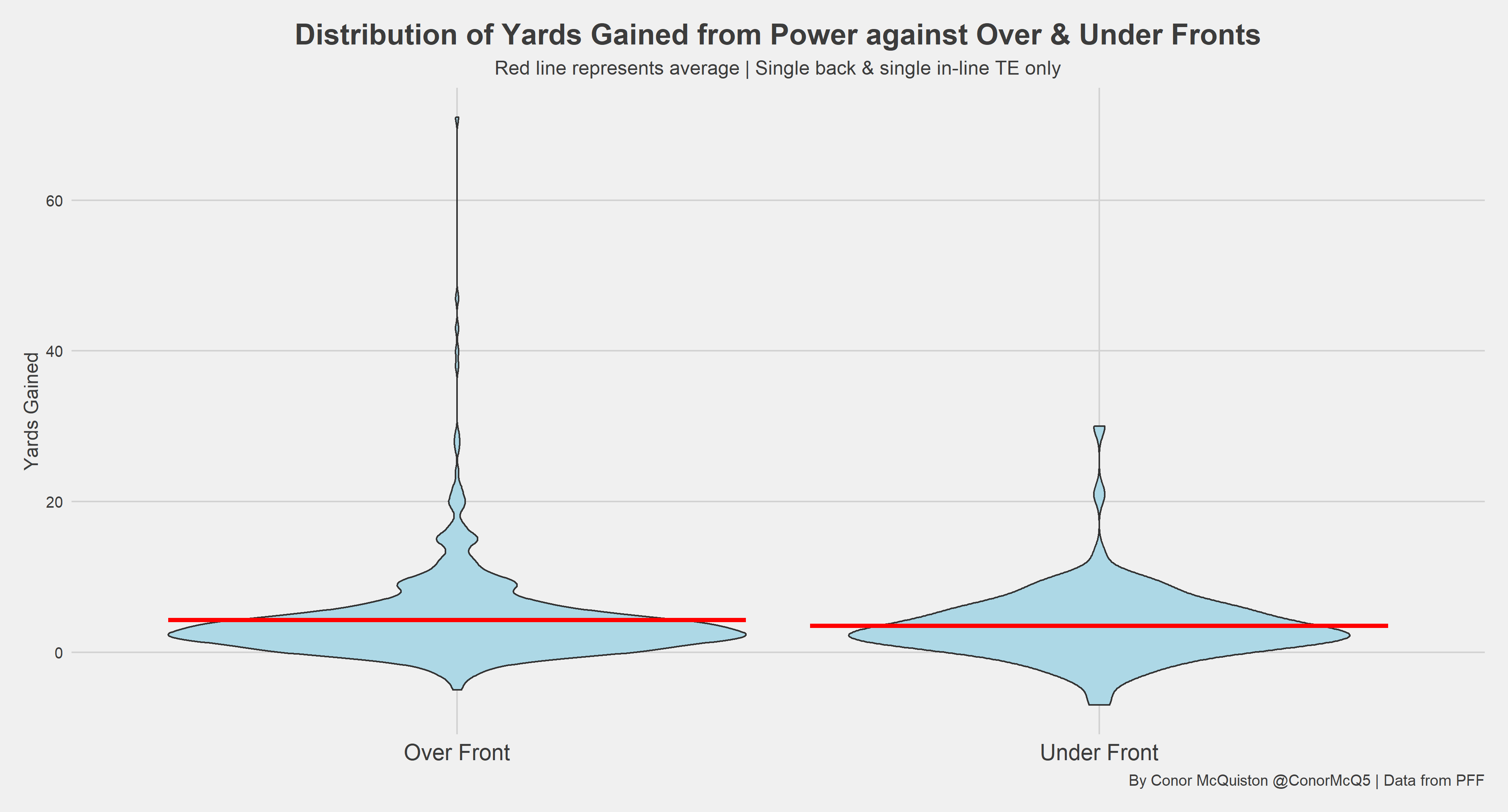

Power is also unique because it needs a kick-out block on an edge defender and can’t be flipped to run at the three- or one-technique when the defense is using an over or under front. If the defense is in an over front, then the offense will be running toward the three-technique and vice versa.

Therefore, the offense’s main choice when using power is whether to run into an over or under front. The theory and scheme suggest that running into an over front (read: toward the three-technique) would be more efficient due to an easier double team on the three-technique and an easier block for the center on the one-technique, as it enables the pulling guard to lead more effectively up to the second level.

The difference is large — the average gain against an over front is 4.28 yards while it is only 3.52 against an under front. However, it is not statistically significant because teams rarely run power into under fronts, doing so only split 13.1% of the time in this split. Thus, we don’t have a big enough sample size for statistical significance. However, given the large gap between the two and how infrequently NFL teams run power against under fronts, we can be confident in asserting that the theory is probably right here.

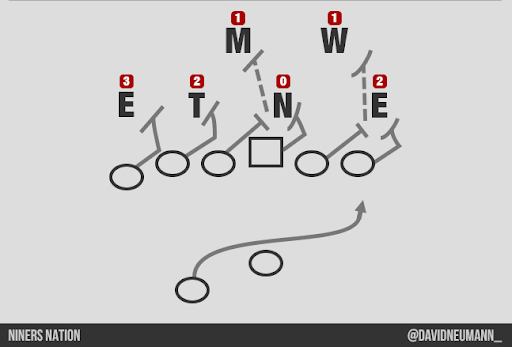

Pull Lead

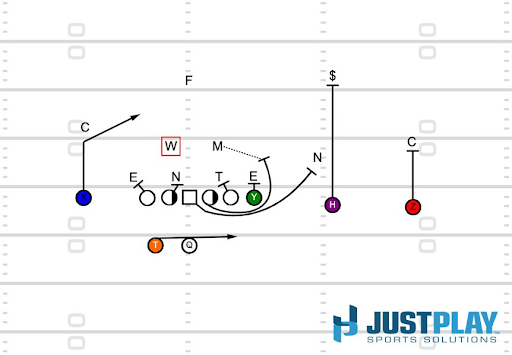

You’re probably not going to see any playbook with a set of runs called “pull lead”, but in PFF’s charting, it refers to any play where one or more play-side offensive linemen pull (the center is considered to be a play-side offensive lineman). These plays are more properly called “pin and pull” (the scheme drawn above) when there is an in-line tight end, or “crack toss” out of four-wide receiver sets.

In pin and pull, any offensive lineman that does not have a defensive lineman across from him pulls while the rest are “pinned” to block the man across from them.

In crack toss out of a four-wide receiver set, a slot receiver will come and crack block the edge defender that is aligned across from the play side offensive tackle while that offensive tackle will pull and act as a lead blocker for the running back who received a toss.

The theory and angles would suggest that it is easier to run toward the one-technique’s side in both cases. For pin and pull, it gives the play-side guard an easier down block, which frees the center to pull. For crack toss, the one-technique will also be down blocked, making him unlikely to get wide enough to chase down the running back on an outside run.

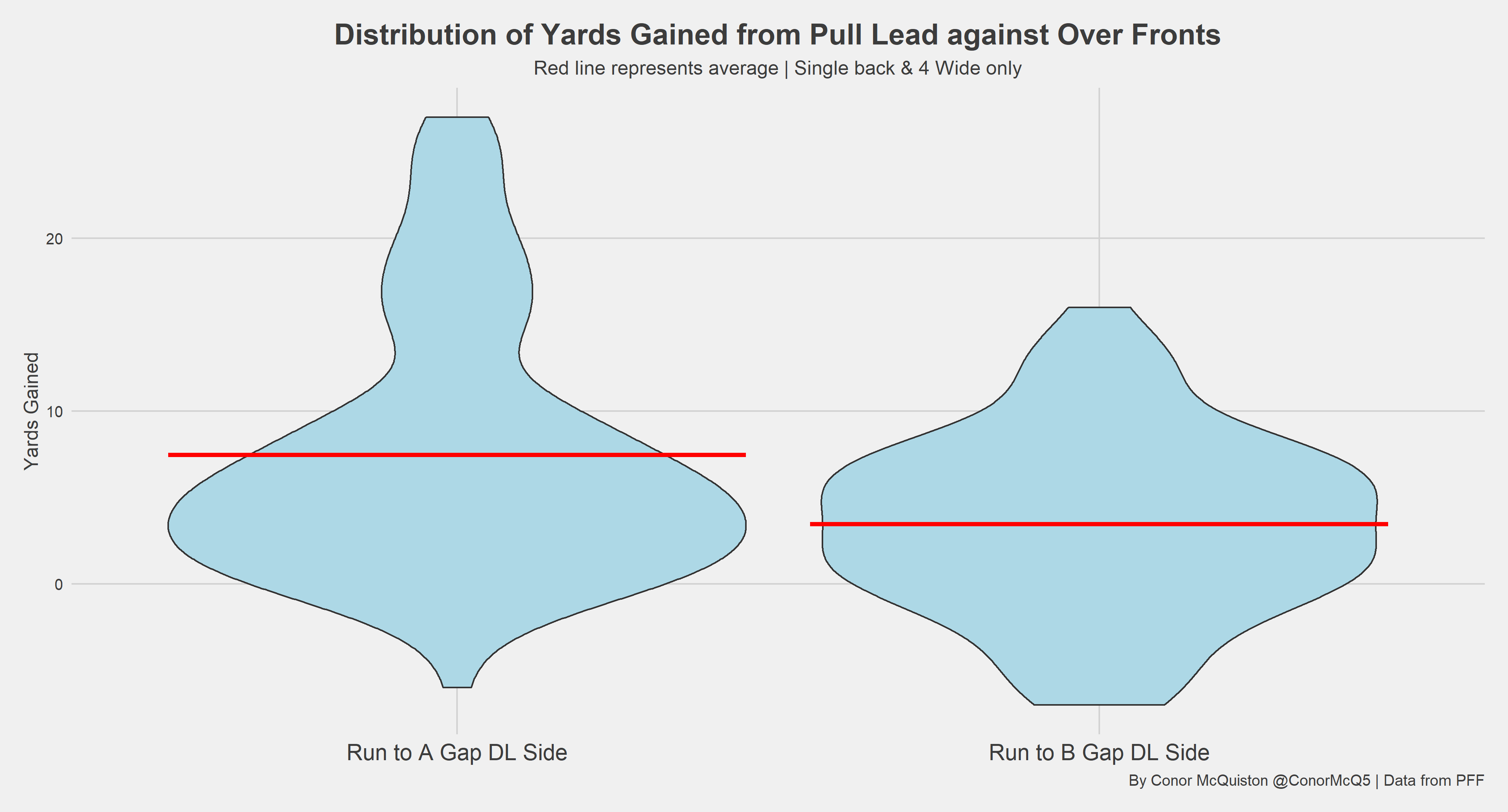

We don’t have a big enough sample to for pull lead concepts against under fronts in singleback and four-wide receiver sets; however, the difference is statistically significant in favor of running to the one-technique side when defenses are aligned in an over front.

Additionally, we don’t have a large enough sample size to make judgements about running against under fronts — both to the field and to the boundary — when in singleback and single in-line tight end sets.

There is a significant sample for running both to the field and boundary against over fronts in those same sets; however, the differences are not large enough to be conclusive. It is worthwhile to note that teams do appear to run toward the three-technique’s side, even if it is not more efficient.

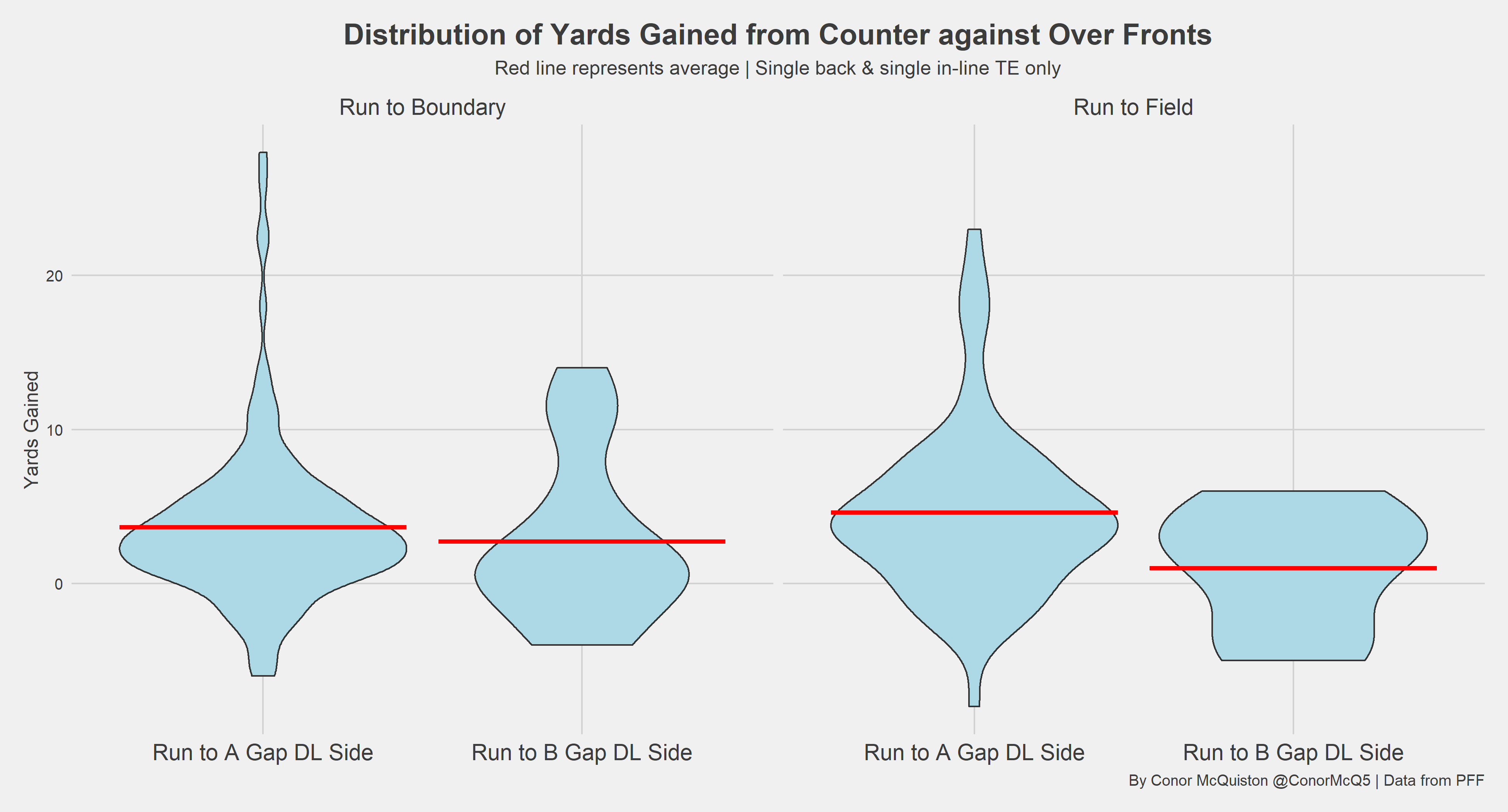

Counter

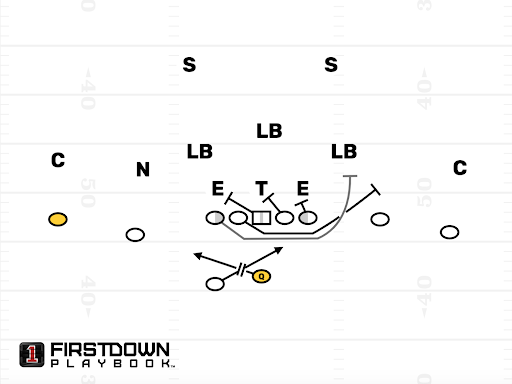

Counter is, in some ways, conceptually similar to power, as the play-side offensive linemen down block in addition to puller lead blocking and a kick out block. The major difference, and defining factor for counter, is that two backside offensive linemen pull. This means it can be run out of four-wide receiver sets as well as with a tight end, although it is a risky counter punch (get it?) to leave two backside defensive linemen unblocked. The theory suggests that it would be better to run this to the one-technique side because the play side guard would have an easier down block.

While in singleback and single in-line tight end sets, counter is run overwhelmingly against over fronts and toward the one-technique’s side, as 72.5% of counter play calls in these sets were run against over fronts while 90% of those calls went toward the one-technique’s side.

The only split with a sizable sample was running it to the boundary against an over front, and it went toward the one-technique’s side 140 times and three-technique’s side just 15 times. The counter runs toward the three-technique’s side aren’t big enough to be statistically significant, but the signal in that disparity is satisfactory to say that it is better to run to the one-technique’s side.

There have only been 66 instances where teams ran counter out of four-wide receiver sets, which is not a large enough sample to say anything of note for our purposes.