Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City arrival in 2016 was greeted by many with a scepticism that the methods that made him so successful in Spain and Germany might not work in England.

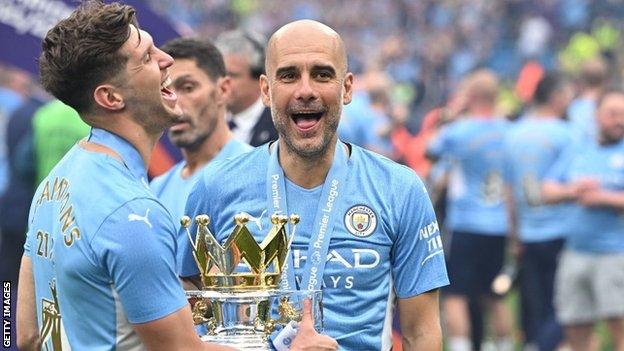

A fourth Premier League title in five seasons, confirmed by an incredible victory over Aston Villa on Sunday, makes a mockery of that initial doubt. There is widespread acceptance now that his approach has changed football in the country dramatically.

A visit to a non-league game, a youth match or even a five-a-side pitch in England would once have been a guarantee of seeing a brand of football focused mainly on winning, with style not an important factor.

But that has changed and Guardiola is arguably the main reason for that. Because of him, we live in different tactical times. Traits such as building from the back, the encouragement to be brave when going forward and the continual ‘possession obsession’ are there for all to see. Not just among the elite but right through the footballing pyramid, all the way down to the youngest of players.

It is no exaggeration to say Guardiola has transformed football.

But what is perhaps less discussed is how English football has changed Guardiola.

The methods honed at Barcelona and Bayern Munich have evolved and will continue to do so following the signing of Erling Haaland. That deal alone says a lot about how Manchester City’s manager has adapted his footballing vision over the past six years.

For City, the Norwegian’s arrival is a sign Guardiola is ready for the next chapter in what is fast becoming a dynasty. The manager’s long-term future is far from certain but he has relished life in Manchester and, despite arriving as arguably the pre-eminent coach of his generation, he has had to adapt to his new surroundings and English football has made him change some of his own views.

He arrived confident in his conviction that you could control a game and set the rhythm for your team with a central midfielder who was neither particularly strong nor overly physical. This is what he had done in the past with Xavi at Barcelona and Joshua Kimmich at Bayern.

But he quickly found out that approach did not work in the Premier League. In England, you need a central midfielder who is powerful in aerial battles and wins 50-50s. Rodri is a good example of what he thinks he needs. Also, he expects his central midfielders to act as a defender when a centre-back moves forward, so they must have the physicality to cope with being in that position.

His view on refereeing is also well known – he is firmly of the belief English referees are far more lenient than their continental counterparts. This has also affected his decision making, as he feels you need players who are physically bigger and stronger to cope with it. If you get knocked down, you’d better get up and be ready to go again as clashes do not get rewarded with fouls as often as they do anywhere else.

Full-backs have been added to help the central midfield, something he started using in Germany. English football has shown him that sometimes you need an extra midfielder and that full-backs can help you take control of the central area of the pitch with the ball, and also help with second balls in central areas when you have to recover possession.

And then there is something Guardiola was concerned about, but is gradually realising he has to accept – that English football, full of the-high octane emotion that comes from the stands, is often played amid a general lack of control, not unlike two heavyweight boxers hitting each other in the knowledge that someone is going to go down, and that more often than not the one with the most quality will prevail.

In the recent game against Newcastle, Guardiola decided to let Joao Cancelo attack and stay very high, forcing his opponent Allan Saint-Maximin to drop deeper. This meant the Magpies winger also had the opportunity to attack the space left in behind by Cancelo. Punch after punch, in the hope that City’s man would win the fight. He did. The champions won 5-0, with Cancelo claiming an assist. It is a tactic that comes from years of experience in the Premier League.

As a perfectionist, Guardiola has focused on eradicating flaws in Manchester City’s game this season.

One of the main areas where he has worked hardest over the past year, and with the greatest success, has been on set-pieces at both ends of the pitch.

In 2021-22, Manchester City have conceded just one goal from such scenarios in the Premier League – a corner against Aston Villa in December – and scored 21 at the other end from dead-ball situations.

But despite the stats, there remains a perception there is a vulnerability to this team. If that is not so much at set-pieces, then what about counter attacks? Their 2-2 draw at West Ham in their penultimate game of the season was a good example of this. Time and again, Michail Antonio and Jarrod Bowen burst through and threatened, with mixed results.

For Guardiola, this is a risk worth taking and comes with the territory if you have so many players in front of the ball. He does set the team up to stop these counters and he has learned to do it well – City have the meanest defence in the Premier League.

In truth, much of the blame for the lack of full control of games can be laid at the door of English football. A scoreline of 2-0 in Spain or Germany is perceived as game over. Not in England.

This is something he has had to get his players to understand – but only after he managed to get a grip on it himself.

Keeping the ball well is not a guarantee that a bizarre turn of events will not occur.

There have been some strange games, not least the 6-3 victory over Leicester in which his side went 4-0 up after just 25 minutes and then conceded three goals in a 10-minute spell in the second half. In the end, a goal from Aymeric Laporte settled everyone’s nerves before Raheem Sterling added a sixth.

One thing Guardiola has come to appreciate over the past six years is that the pressure put on teams by fans in England is unlike anywhere else in the world and how you deal with it ultimately defines you.

In moments such as these, it is possible that there is nothing that can be done to stop a change of dynamic. The Real Madrid game in the Champions League semi-final was a case in point – if one of the six chances City had at Etihad Stadium, or one of the two Grealish had late on at the Bernabeu, had been converted, the story would have been different. Guardiola accepts that sometimes control and possession is not enough. Tactical acumen takes a temporary back seat to raw courage as emotions take over and it becomes a case of ‘all hands to the pump’ as an opponent piles forward.

This is one area where he knows things can be improved. Ruben Dias displays a calmness and clarity in his decision making in moments of stress and panic. He is an example to follow.

What about Kevin de Bruyne? He is a truly brilliant player who knows what he has to do and does it with consummate skill, but to reach the level of Karim Benzema, Lionel Messi or Cristiano Ronaldo, he should be more present in the sharpest, most brutal of moments.

Up until now, Guardiola has tended to favour intelligence, adaptability and technique over huge personalities when building teams.

But every successful side needs leaders beyond the one on the bench. It seems to me the signing of Haaland for £51.2m from Borussia Dortmund is an admission not just that they need his goal touch, but equally that they require him to make the difference in the moments where competition is mostly level – in semi-finals, finals and big domestic games against Liverpool.

And in signing the Norwegian, City have recruited a genuine superstar, with a force of personality to match his talent.

It is not guaranteed though that City can go from winning most games to winning them all. Who can? Guardiola has dominated domestic titles and his team are now regulars in the latter stages of the Champions League (which was the requirement from the club owners) without a regular goalscorer or a decisive player in key moments like Harry Kane or Mohamed Salah.

Guardiola and director of football Txiki Begiristain have known for a long time that City needed a top striker and a top personality. For two windows, they tried to sign Kane, without success.

The expectation is that Haaland will be that kind of player and it is likely City will alter the way they play to accommodate him.

Guardiola has long placed a lot of emphasis on his team working in the wide areas of the pitch, trying to establish numerical superiority before finishing things off with the arrival in the box of the midfielders. Often crosses are ignored as they do not have players to head those balls in.

Overall, this has worked brilliantly, but for some time City have lacked efficiency in the penalty area – no side has squandered more chances than they have in the past four years. Haaland has been bought to change that.

His arrival will probably mean less emphasis on moves in wide positions, with build-up play coming more from a central area, and with a greater focus on players arriving into the box.

And we may see even more of a transitional game.

At Barcelona, Guardiola used to say the team should pass the ball 15 times before starting an attack, that way ensuring all the players were in the positions they should be in. That was the basis of his positional game. But in England, he has learned how quick transitions can be decisive.

It was something he also explored during his time in Germany, but he has taken that to a new dimension in the Premier League. De Bruyne has been key to that, a player whose incisive passing helps break down those sides that defend in a deep and compact way, the most-used tactic of City’s rivals.

Guardiola is a passionate advocate of an approach which destabilises the opposition by constantly moving the ball around before finding the killer pass. But he has come to accept there are more and more instances where playing a much quicker game is the best option, because that is when the opposition are at their most disorganised.

This is not a change in approach, just a required adaptation.

Haaland will thrive on the quick transitions but will also relish the opportunities to get into the six-yard box for a side who create more chances than anyone else in Europe. He has been told he will be, more often than not, City’s ‘get out of jail free card’.

The elephant in the room when discussing a City future under Guardiola is that his contract expires in 2023.

Gossip has it that Haaland was told his arrival would make it easier for the 51-year-old to decide his future, although that certainly would not have come from the manager himself and the club denies that point was discussed in the negotiations.

Now is probably not the time to talk about that, not least because Guardiola is still affected by the frustrating loss to Real Madrid.

One thing that is certain is that when the Spaniard makes up his mind, it won’t be until he has had a long break, cleared his head and convinced himself whether or not he has the energy to carry on at City.

It won’t be the lack of a Champions League win that decides the matter for him either way. He doesn’t believe he has done anything less than really well at Manchester City.

He knows that winning the Champions League would be the cherry on top of the cake and is also aware that getting the best out of the same – or similar – group of players gets harder and harder every year. Maybe obtaining the ‘precious title’ (Lionel Messi’s words) will be done by the next manager using the foundations he has put in place.

But for now, he isn’t talking about that. Right now, there is no space or strength to look forward just yet. Only to celebrate and rest.

Guillem Balague writes a regular column throughout the season and also appears every Thursday on BBC Radio 5 Live’s Football Daily podcast, when the focus is on European football.

You can download the latest Football Daily podcast here.