The 8x10s still arrive in Dave Freisleben’s mailbox every so often. As a right-handed pitcher in the 1970s, Freisleben spent six seasons in the big leagues with three different teams. But these photos sent by autograph-seekers depict him in the uniform of a team he never even played for.

A team nobody ever played for.

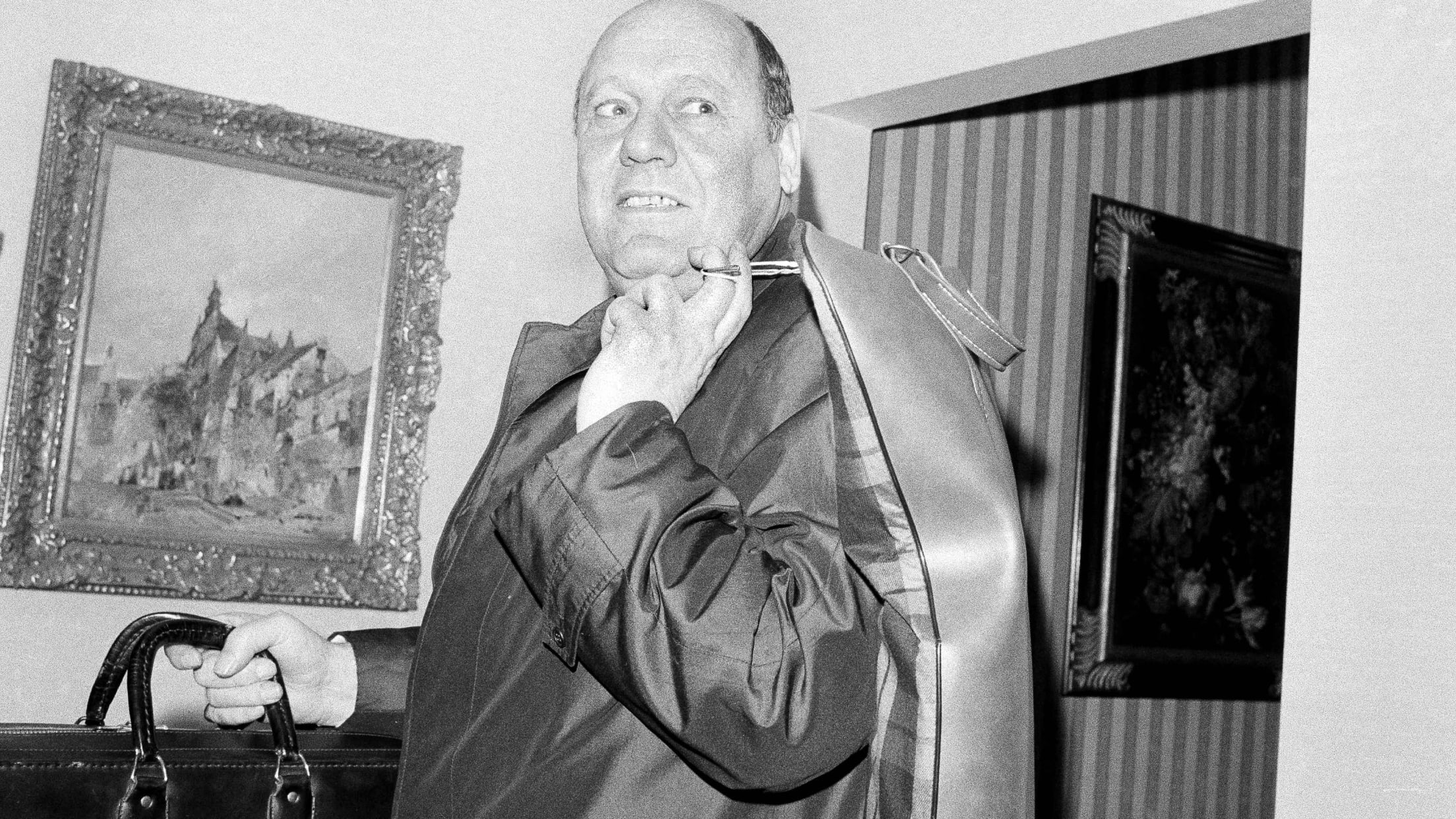

The now-70-year-old Freisleben is depicted in the photos wearing the uniform of a National League team that was supposed to play in Washington in 1974. And though he can’t tell you why he was the one selected for the photoshoot or even remember who asked him to participate, Freisleben can proudly proclaim that he is the only person known to have worn this odd attire.

“It’s weird,” Freisleben says of his unique status in Major League history. “I don’t go crazy over it, but it’s pretty cool.”

The uniform itself is, um, kind of ugly. True to its times, it is free of buttons or a belt. The powder-blue road jersey and pants feature red, white and blue stripes along the V-neck collar, sleeves and waistline, and the three-tone cap features a red “W” adorned by a blue star.

But while the uniform itself is uninteresting, the story behind it is one of baseball’s biggest what-ifs. It’s the story of how the San Diego Padres – a team that recently finished its 52nd season in MLB – were almost one of the shortest-lived squads in modern history.

Back in their fifth season of existence, the Padres were placed on the checkout lane and sold to a grocery store magnate who intended to move them to the nation’s capital. And if not for a hamburger helper who swooped down from the Golden Arches to save the day, a move to D.C. or elsewhere just might have happened.

What follows is the tale of how the 1974 Washington baseball team (a nameless entity long before the city’s NFL entry played with a placeholder) got so far as to have uniforms, trading cards and a season schedule … but never actually took the field.

It is a team that survives only in that Freis-frame.

* * * * * * * *

Dave Freisleben models the extremely ’70s Washington unis.

Everything stemmed from the approval of the A’s move from Kansas City to Oakland in October 1967.

At that time, the American League, looking to appease Missouri Sen. Stuart Symington, cemented plans to add two new teams in Kansas City and Seattle. And though the two leagues operated somewhat independently in those days, the AL’s expansion forced the hand of the NL, which voted at the 1967 Winter Meetings to also increase its number of clubs by two.

Thus, the sales pitches and politicking began. San Diego, Montreal, Dallas-Fort Worth, Buffalo and Milwaukee were seen as the viable frontrunners for a new Senior Circuit squad, and the vote on the two winners was held at a meeting of NL owners in Chicago on May 27, 1968.

Montreal was chosen swiftly and unanimously. The second selection was a matter of deeper debate, with nine initial votes going to Buffalo. Were it not for Giants owner Horace Stoneham, who in the 1950s had moved his team from New York to San Francisco, holding out for another West Coast club, Buffalo likely would have been the victor. But after much deliberation and arm-twisting, on the 18th and final ballot, San Diego and its proposed ownership team featuring local businessman C. Arnholt Smith and former Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi, won out.

“The action in Chicago by the NL owners,” Smith told reporters, “is another expression of confidence in the great future that lies ahead for San Diego.”

Within just a few years, however, that confidence gave way to doubt.

* * * * * * * *

“He ruined the lives of so many people and he only served eight months in a county jail as punishment.”

– Peter Bavasi on C. Arnholt Smith

That the hastily assembled team dubbed the Padres (a name adopted from the city’s Pacific Coast League franchise that had been in San Diego since 1936) would struggle on the field was a given. And indeed, the Padres did struggle, to the tune of a .367 winning percentage in their first four seasons.

More alarming, though, was their struggle to generate revenue, as Peter Bavasi, Buzzie’s son and a prominent member of the team’s front office, recalls in an email interview.

“Almost from day one, after the irrational exuberance resulting from the Padres franchise award in 1968, it became clear to Buzzie and to the club’s senior staff that this was not a city ready for a Major League Baseball franchise,” Bavasi writes. “We did not have a corporate base for season tickets and sponsorships, nor the media outlets, and we were hemmed in geographically by Mexico to the south, the ocean to the west, the desert to the east, and the Dodgers and Angels to the north.”

The Padres’ problems were exacerbated by unscrupulous money handling of their majority owner.

Smith had paid the $10 million expansion fee to launch the franchise, but he wasn’t willing to spend the money needed for player development. The younger Bavasi, whose first role with the Padres was farm director, worked under Smith for more than five years and says he never even met the man.

“He was a crook and a convicted felon who siphoned off the ballclub’s homestand ticket deposits,” Bavasi says of Smith.

Buzzie Bavasi on his way to meet with the Commissioner to discuss a potential move.

Smith would, indeed, be convicted in May 1979 on one felony count of grand theft for stealing $8.9 million from his securities company, Sovereign State Capital. He would serve only eight months of a one-year sentence. And earlier in the 1970s, the United States National Bank, which Smith owned, suffered what was, at the time, the largest bank failure in history due to excessive loans to Smith-controlled companies.

When the bank went under, so did the pension plans of Padres employees.

“He ruined the lives of so many people,” says Bavasi, “and he only served eight months in a county jail as punishment.”

Even before Smith wound up in court, there were signs that he was not fit to own a Major League team. At one point, early in the club’s existence, players were asked to wait until Monday to cash checks they received on Friday.

The team did not have enough fans to offset those fiscal problems. Back then, San Diego had a population just north of 1 million. Smith had told reporters, “If everybody in the city of San Diego attends one game, we’ll do all right.”

Alas, not everybody attended one game.

The Padres drew an average of only 7,179 fans per game at San Diego Stadium in those first four seasons. By comparison, their NL expansion peers, the Expos, drew more than twice as many fans, with an average of 15,890.

“Attendance was an issue right from the start,” says longtime Padres broadcaster Bob Chandler. “And things weren’t going any better at the beginning of ’73.”

They sure weren’t going well for Smith. On May 5, 1973, it was revealed that the Internal Revenue Service was after him for $23 million in unpaid taxes.

So it was that on May 27 — exactly five years to the day after the vote that had awarded San Diego its franchise — Chandler and his broadcast mate Jerry Coleman were told to report to an all-employees meeting after a Sunday doubleheader against the Phillies.

“We were informed, that the Padres were being sold to a Washington, D.C. grocer and would move to D.C. at the end of the season,” says Chandler. “Or maybe even during the season.”

That “grocer” was Joseph B. Danzansky, president of Giant Food Inc.

* * * * * * * *

“You can be sure all of us in the Washington metropolitan area would enthusiastically welcome a National League team.”

– President Richard Nixon

As a leading member of Washington’s business establishment Danzansky had, just a few years earlier, fought to keep baseball in the District prior to the departure of the AL franchise known as the Senators. Now, he had headed up a group intent on bringing it back by buying the struggling San Diego squad and moving it more than 2,000 miles away.

With what was, at the time, a record purchase price of $12 million — $2 million more than a group headed by George Steinbrenner had paid to buy the Yankees just a few months earlier — the deal was in place. And though Padres employees were instructed to keep the deal a secret at that May 27 meeting, the news was everywhere by that evening, meaning the final 53 home games on the season schedule (if the Padres even remained in San Diego that long) would be funereal affairs.

“I know it will kill interest and attendance here,” Smith told reporters.

Just like that, the Padres were baseball’s lame ducks. But the Danzansky deal was contingent upon the resolution of legal issues. The team was in the fifth season of a 20-year stadium lease with the City of San Diego and had other commitments to various vendors. Quickly, it became clear that those issues would prevent an in-season move, at the very least.

“Any potential buyer seeking to own the Padres realized that moving the club out of San Diego would be very difficult legally, financially and practically,” Bavasi writes. “The city was gearing up for a massive breach of contract lawsuit against the club and the National League.”

While those hurdles were massive, the thought of San Diego interests stepping in to save the franchise appeared remote at the time.

“I’d be the happiest man in San Diego if the team were to remain here,” Smith told reporters. “But it seems unlikely. How can someone else make it work if we couldn’t?”

And so the Washington possibility was taken seriously. By year’s end, it would be unanimously approved by the 11 other NL owners, with a 1974 schedule drawn up. (Washington would have faced the Phillies on Opening Day at RFK Stadium at 2:30 p.m. ET on April 4.)

It also got a push of support from President Richard Nixon.

“I just want to cast my own vote in favor of returning major-league baseball to the Nation’s Capital,” Nixon wrote to NL president Chub Feeney in September, mere weeks before the “Saturday Night Massacre” and the initiation of the impeachment process that would unravel his presidency. “You can be sure all of us in the Washington metropolitan area would enthusiastically welcome a National League team.”

The proposed team never did nail down a name. Unlike the two most famously ill-fitting monikers that are a product of NBA franchise relocation (Los Angeles Lakers and Utah Jazz), “Padres” was not going to survive the move to Washington.

Another P-word — “Pandas” — was given a passing thought, in homage to the giant pandas housed at the National Zoo that had been given to the U.S. as gifts following Nixon’s visit to China in 1972.

More genuine consideration was given to “Nationals,” a nod to Washington’s first professional baseball team in the 1800s and the name often used interchangeably with “Senators” in newspaper references to the AL franchise in the 20th century.

“Stars” was also in the mix — a strong enough possibility that the artist who designed the mock-up cap worn in the Freisleben photos included a star-like image on the “W.”

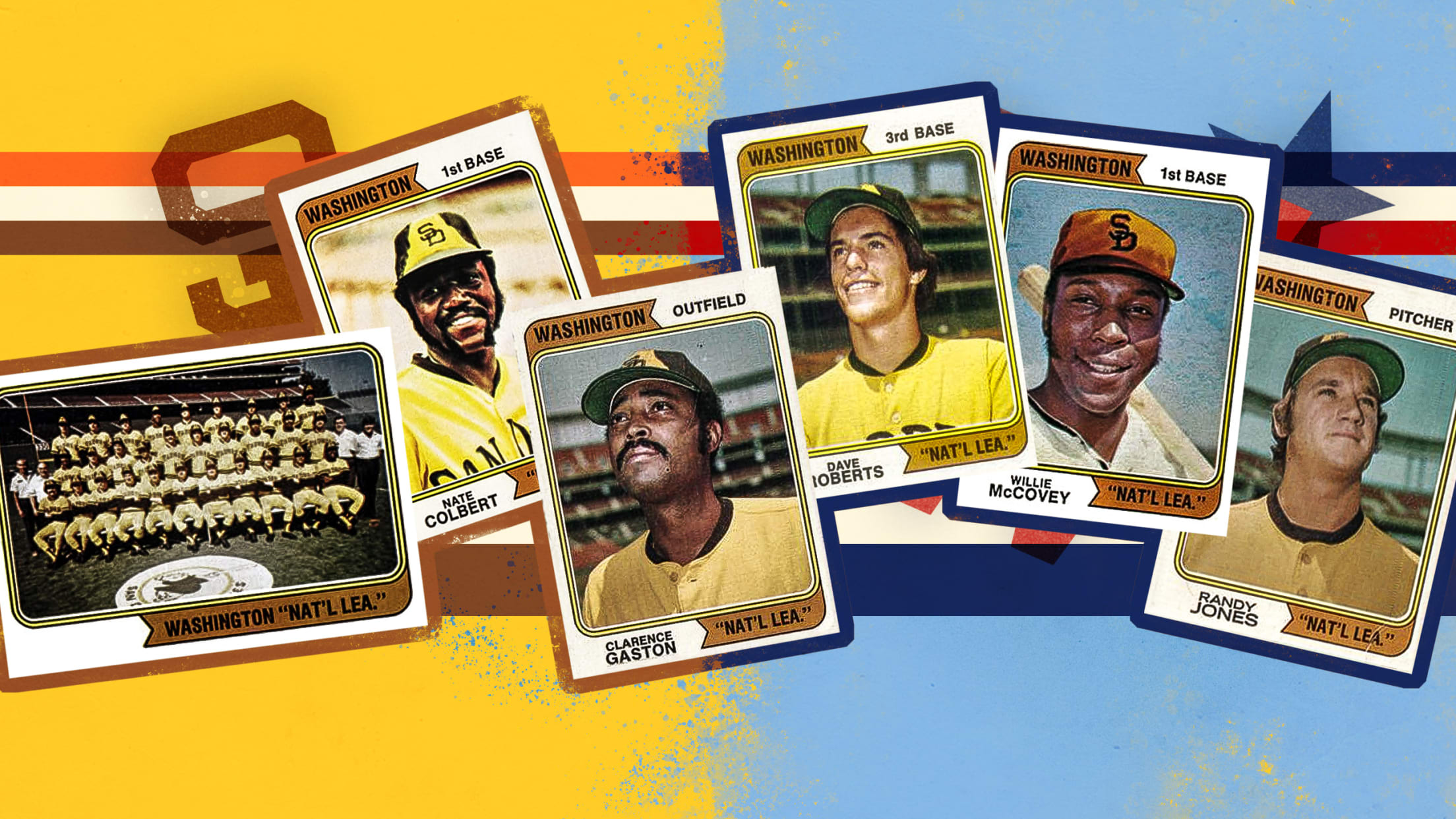

But neither Nationals nor Stars — and certainly not Pandas — was given final approval. And so, in the winter after the 1973 season, when the fate of the franchise was still not known, Topps’ initial printing of its 1974 cards identified Padres players as members of a Washington team known only as “NAT’L LEA,” for National League.

There are 15 cards in the set, including one featuring Hall of Famer Willie McCovey and another in which Freisleben appears among four rookie pitchers from around the league.

“That’s an error card,” Freisleben. “I’ve saved some of those.”

As of this writing, a full set of the “Nat’l Lea” cards was available on eBay for $195.

* * * * * * * *

Topps cards for a team that never existed. (Images via tcdb.com)

The only official decision with regard to the Washington team name was that the “Senators” would not be elected to a third term.

Washington’s AL history as the Senators had been underwhelming, to put it charitably. Though the initial iteration of the Senators did win a World Series in 1924, Washington was known more for being, as San Francisco Chronicle columnist Charles Dryden playfully put it, “First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.”

The charter AL franchise that would become the Minnesota Twins and the 1961 expansion franchise that would become the Texas Rangers finished 31 of their combined 71 seasons in last or next-to-last place. Only once – in 1946 – did either team manage to draw more than 1 million fans in a season.

Near the end of a 63-96 season in 1971 – after Danzansky’s bid to buy the Senators was deemed “insufficient” by the AL owners and Commissioner Bowie Kuhn – owner Robert Short announced the team would be moving to the Dallas-Forth Worth metroplex. That same year, Danzansky also attempted to buy the Indians from Vernon Stouffer and move them to Washington, but the AL instead approved a sale to Nick Mileti, who kept the team in Cleveland.

So for Danzansky and for Washington, the Padres pact was a new and very real chance to try again.

From the time the sale agreement was made through the conclusion of the 1973 season, Danzansky was given the leeway to approve or reject player transactions (he evidently signed off on San Diego’s first-round draft selection of a University of Minnesota outfielder named Dave Winfield). Danzansky also had eyes on landing Frank Robinson, who at the time was playing for the Angels, as his player-manager, which would have made Robinson the first Black manager in MLB history. (Robinson would still achieve the feat with the 1975 Indians.)

In the late fall, Peter Bavasi, who by that time had been appointed the Padres’ general manager, was dispatched to D.C. to work with Danzansky’s group on the transition process. Bavasi was invited to stay on as the Washington team’s general manager after the completion of the transaction.

“Joe and his associates were terrific people, very enthusiastic, very supportive, very generous,” Bavasi writes. “I spent lots of time at RFK [Stadium] and walked the neighborhood around the ballpark, getting to know the good people nearby.”

It was freezing in D.C. during Bavasi’s trip, and he had packed only a raincoat and some warm-weather suits more appropriate for San Diego weather. So Danzansky lent him a camel-hair topcoat. When Bavasi returned to California after a two-week stay, he shipped the coat back to Danzansky with a note of thanks.

Danzansky sent it right back.

“Please keep this coat,” the prospective owner wrote. “I have every confidence that you will need it someday when you come back east!”

Danzansky was right. Just not in the way he intended.

* * * * * * * *

Bavasi meets with the other National League teams before a potential sale

Padres owner C. Arnholt Smith had a deal in hand to receive $12 million from Danzansky’s group in exchange for his baseball team. But in late 1973, the City of San Diego threatened to sue the Padres for $84 million for breaking the San Diego Stadium lease and other damages.

When NL owners voted their approval of the D.C. sale on Dec. 6, 1973, San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson responded, “We’ll see you in court.”

It never got to that point. Danzansky lined up insurers to protect himself and the league from the lawsuit, but the arrangement required Smith to pay the steep premiums. That certainly wasn’t going to happen.

By that point, Smith had already made an effort to avoid the legal dispute and keep the team in San Diego by selling to a different group headed by horse racing track owner Marjorie Everett that also included composer Burt Bacharach. But out of concern regarding Everett’s gambling interests and her testimony in a bribery and conspiracy trial of an Illinois judge, NL owners just – to borrow a phrase from one of Bacharach’s most famous songs – walked on by that proposal.

So Smith and the Padres were in a really tough spot entering 1974. They had no remaining suitors. They had no radio or television contracts in place. They even had to ask for (and received) a $71,000 advance from the City of San Diego to prevent 10 of their players from becoming free agents.

Spring Training was fast approaching, and team players and employees had no idea where they’d call home.

Until one day, aboard his 100-foot yacht off the coast of Fort Lauderdale, McDonald’s chairman of the board Ray Kroc read in the newspaper about the San Diego/Washington financial fiasco. Kroc had previously been rebuffed in his effort to buy his hometown Cubs, and in that moment, much like when he was a milkshake mixer salesman who visited the McDonalds brothers’ restaurant for the first time, he sensed an opportunity.

“You know, honey,” Kroc said to his wife Joan, “I think I’m going to buy the Padres.”

Joan knew nothing about baseball.

“Why would you want to buy a monastery?” she asked.

That small bit of confusion aside, the rest of the process was amazingly uncomplicated. A lunch meeting was quickly arranged between Kroc and Smith.

“How much do you want for the team?” Kroc asked.

“Twelve million,” Smith replied.

“Deal,” Kroc said, and the two shook hands.

It was arranged in about the time it takes to get a Happy Meal at a drive-thru. Smith would later say that he probably could have asked for and received double.

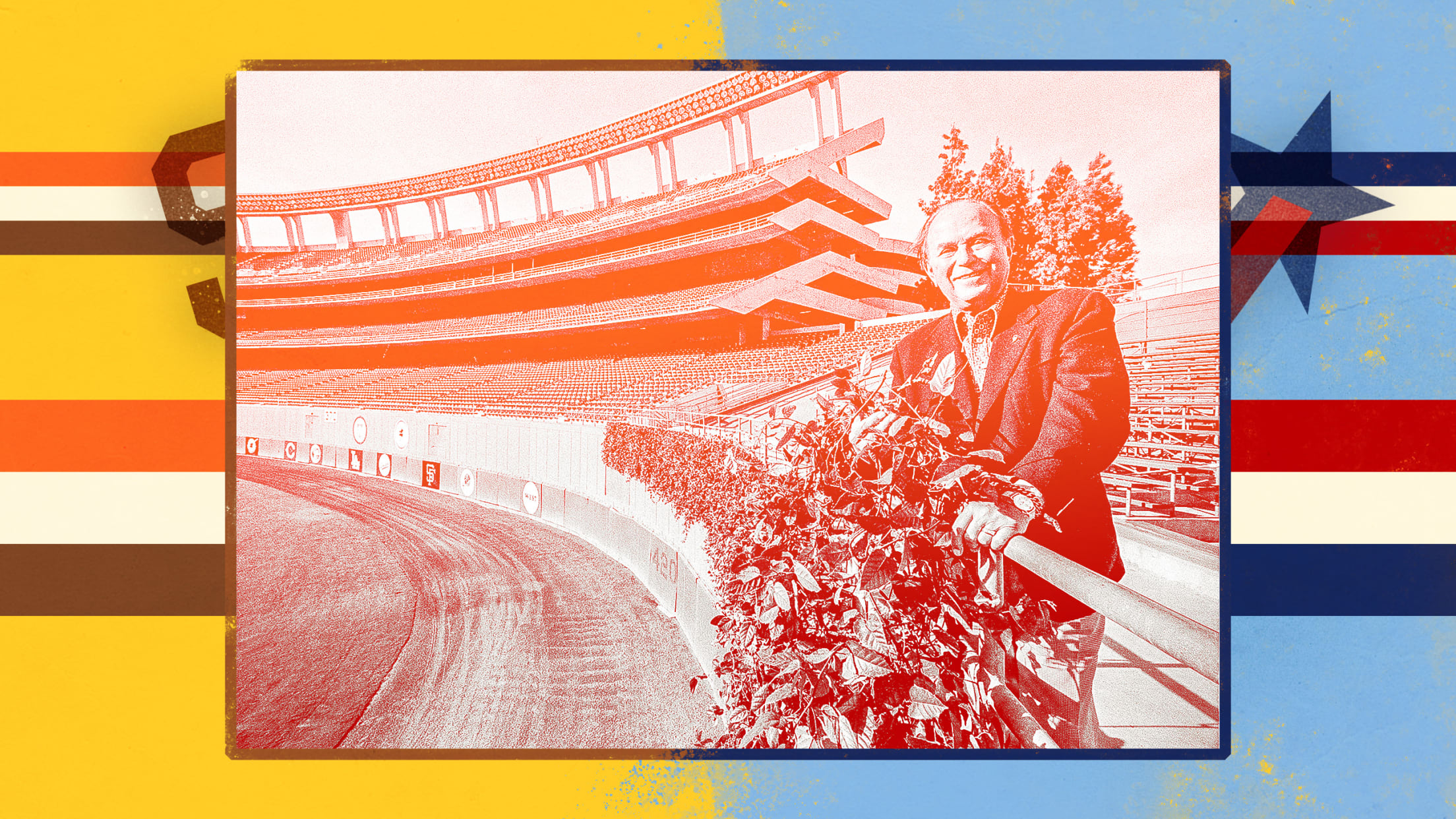

So the team run by a crook was saved by a Kroc, and the Mickey D’s mogul forever endeared himself to San Diegans at his first home opener as owner.

The Padres were trailing, 9-2, when Kroc stormed into the press box and grabbed the microphone for the public-address system.

“Fans, I suffer with you,” he said to the crowd of more than 39,000. “I’ve never seen such stupid ballplaying in my life.”

Players and the league didn’t love that, but the fans did. The Padres drew over 1 million fans for the first time that year and each of the six years afterward. They would not finish higher than fourth place until 1984 – the year Kroc passed away – but they wore a jersey patch in his honor that season and reached the World Series.

“Ray was a blessing to the ballclub and to everyone working at the Padres,” Bavasi writes. “He was determined to make the Padres a big league operation. And he did.”

* * * * * * * *

Ray Kroc takes in the Padres’ center field ivy in 1979.

As for the District, well, the wait for another Major League franchise went on for quite a while.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn devised a plan in 1975 in which every Major League team would play two home games at RFK Stadium, but it didn’t transpire. Washington was also one of the finalists for the 1977 expansion in the AL, but those franchises went to Seattle (which had lost the Pilots after just one season in 1969) and Toronto.

Incidentally, the first general manager of the expansion Blue Jays was none other than Peter Bavasi, who moved from San Diego to Toronto for the job.

“Joe was right,” he writes of Danzansky. “I did need that coat.”

As fate would have it, it was not the Padres but the other 1969 NL expansion team – the Montreal Expos – that moved to D.C., in 2005. Frank Robinson got to manage Washington’s NL team, after all, just as Danzansky, who passed away in 1979, would have wanted. And the Nationals name did, indeed, resurface.

By then, Freisleben, whose big league career ended in 1979 with Bavasi’s Blue Jays, was long out of baseball. These days, he spends much of his time at a country club near his home in League City, Texas. Recuperating from his third shoulder surgery (a perhaps unavoidable injury for someone who, in his rookie season with the Padres, had outings of 13 innings and 11 2/3 innings in the very same month), Freisleben had to put his golf game on hold recently. But just the other day, somebody introduced him to another member of the club – a gentleman named Fred Zeidman, who is a partner with the Washington Nationals.

“I showed him a picture in my phone of me wearing the uniform,” Freisleben says.

It’s one of the few pieces of evidence we have that, long before the Nationals, there were the “Nat’l Lea”guers.